American-Iranian chef and cookery writer Samin Nosrat may have been catapulted to culinary fame with her debut cookbook Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat – and a hit Netflix series by the same name – but success sent her spiralling.

“That thing that I’d been single-mindedly chasing basically my whole life, I found it, I got it, and still had that loneliness inside, that feeling of ‘it’s not good enough, I’m not good enough’,” shares the 45-year-old.

The 2017 publication, which flipped the script on traditional recipes and taught home cooks how not to rely on them, and instead cook more instinctively, is somewhat considered a modern classic.

But the experience “was actually really destabilising and sent me into a big depression”, says Nosrat.

“The publication of Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, and the show was so much bigger and longer than anything I could have anticipated or imagined. You get a whole cloud of activity around you and everyone wants to talk to you, [there’s] opportunities and shiny objects and they love you so much and it feels good.” It led to a four-year-long column in the New York Times and new-found financial stability (“Before that book came out I was always striving so hard”).

But, she reflects, “I was therapised enough to know that was not actually about me, that’s not a reflection of me. But it’s really hard, when you’re in the middle of it and when it goes on for years, for it not to mess with your head.”

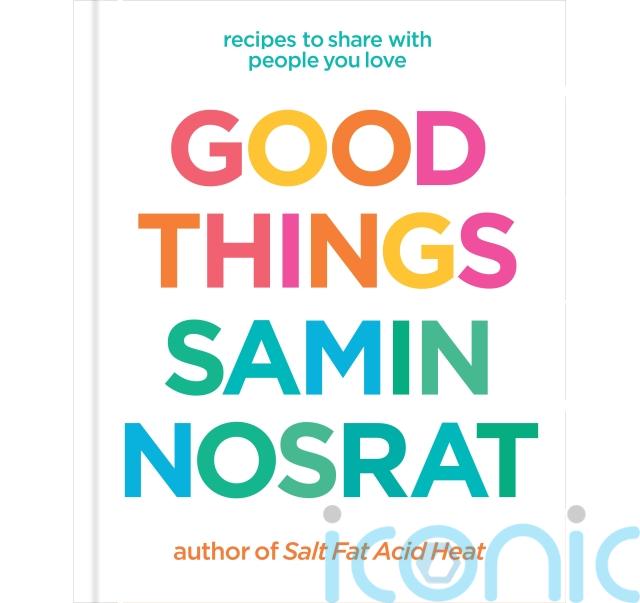

And then in the expanse of time and space during the pandemic, she says she had to really “confront” her life. It’s one of the reasons it took her eight years to write her second, much anticipated, cookbook, Good Things – a more personal offering and, this time, a lot more recipes. Although fans will be pleased to know Nosrat is still making up her own rules. She admits having recipes at all felt “hypocritical” at times.

Persian influence is, of course, at the heart, but her flavours stretch far and wide. You’ll find joojeh kabob roast chicken and preserved lemon and labne cake, next to made-from-scratch focaccia and spaghetti cacio e pepe, as well as handy techniques generously peppered throughout Nosrat’s storytelling.

It’s really a manifestation of the journey she’s taken to “redefine” her relationship to cooking, through mental health struggles and a difficult time when her dad died in 2022, after a brain injury.

“I very much had this face-to-face confrontation with mortality and the limits of time,” she says, of her dad’s death. “I’ve always had this thought of, ‘Maybe if I’m good enough and I work hard enough, if I’m sacrificing all this stuff and not having a good time now, at some point I’ll meet this goal that the universe has set out for me, and then I can have fun, and then I can be happy’.

“In these last few years, I’ve realised there’s no invisible goal, there’s no force that’s going to tell you, ‘OK, now you can enjoy life – you have to do that now.”

For some time, she says, food no longer held the same joy it once did, but she rediscovered its “source of meaning” in her life. “Even if I’m depressed, I’m food motivated.”

It was a slow and steady process. “I had to give myself time and space, to be bored and be slow and boring. I would get really quiet and find something little that interested me. I watched a show called Taco Chronicles and then went down a rabbit hole trying to reverse engineer tacos al pastor at home. Which led me to the next thing.”

Cooking for pleasure, not just for necessity, obligation and convenience, is completely underrated, she believes. Everything down to the “shopping, cooking, preparing, cleaning – I think even these basic tasks can be a source of pleasure in and of themselves.

“At this point, everything’s become artificial intelligence, like we’re so divorced from the most basic parts of life. To be able to do this menial task, picking up a cauliflower, slicing it, roasting it, gives you an opportunity each day to have a sensory experience,” she says, “also to have what is a very human necessity of doing something from start to finish.”

The two things that are really “grounding” in her life are gardening and cooking.

“When I’m cooking, I have to be completely focused on what I’m doing [or] you’ll burn yourself, you’ll cut yourself, you’ll add the wrong thing. And same with gardening, you’re elbow deep in dirt or a pot of potatoes. Then, what are you not doing? You’re not on your phone, you’re not on a screen, you’re not in your head. So it very much pulls me back into my body, into the present moment.”

Hosting weekly dinner parties at her house soon became an “anchor” of her social life – “that absolutely gave me a real sense of meaning. But there’s a little bit of a martyr complex, I want everything to be so perfect. I started to realise it was about control for me, and this idea that I had about making people feel comfortable, but actually I was making them feel uncomfortable because I was getting up 500 times and doing all the dishes. Like, I’ve invited you over to my house, but I’m not actually spending any time with attention on you.”

She realised the “more generous” way to host is to set things up ahead of time, to be more present with her guests.

But the tendency to ‘people please’ has a lot to do with her experience growing up, she notes. “It’s immigrant child perfectionism”.

Born in San Diego, her parents arrived in California from Iran in the Seventies, “I grew up very much feeling like I was different and an outsider. I was a brown kid in a very white world and I think one of my core worries in the world is feeling different and separate and alone.”

Meal times were an important link to her roots though. “My mum, the main way she gave me and my brothers a relationship to our ancestral culture was through food.”

She’s definitely felt a “loss and disconnection” within her own family and ancestral lineage though, she says, so it’s been a struggle to find her ‘place’ to feel at home in the world.

Today she lives by herself in Oakland, California, among a courtyard of homes with her neighbours – “so both alone and together” – and that connection has become key.

“As I get older, I’ve worked really hard to invest in friendships and in solid relationships with people around me. I’ve just realised, oh, for me [as a child of immigrant parents], it looks different, I’ve had to build something original for myself today.

“I wasn’t handed a place to belong. I had to build a place to belong.”

Good Things by Samin Nosrat is published in hardback by Ebury Press, priced £30. Photography by Aya Brackett. Available now.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.